Sarracenia Spiketail (Zoraena sarracenia) at Middle Branch Bog (Natchitoches Parish, LA), 18-March-2011, photo by John C. Abbott.

December 2025 Species of the Month:

Sarracenia Spiketail (Zoraena sarracenia)

This month’s DSA species focus is the Sarracenia Spiketail (Zoraena sarracenia), formerly Cordulegaster sarracenia. The Sarracenia Spiketail is the most recently discovered species new to science from the United States. It is sometimes nicknamed “the Pitcher Plant Spiketail,” and is approximately two-and-a-half inches long (6.35 centimeters). The Sarracenia Spiketail is an early spring dragonfly found in bogs—often alongside the pale pitcher plant—in eastern Texas and western Louisiana. Read on to learn about its discovery from our guest blogger, John Abbott, who, together with Troy Hibbitts, described the species.

A Boggy Adventure

Back in April 2010, Nick and Ailsa Donnelly came to Austin—where I was Curator of Entomology at The University of Texas—to visit their son Andrew and his family. They made this trip once or twice a year, and we’d often plan a field adventure around it. This time, our sights were set on the Lower Rio Grande Valley. Greg Lasley joined us, and the four of us headed south, eager to see what we could find.

The weather, however, had other plans. It turned into a soggy trip to South Texas. On April 19, we stopped at the Santa Margarita Ranch near Roma and managed to find a few Sulphur-tipped Clubtails (Phanogomphus militaris) and Powdered Dancers (Argia moesta), but that was about it. The skies stayed gray, and the rain kept us grounded. By the next day, we were huddled in my car, trying to stay warm and dry, wondering what to do next.

That’s when I mentioned an email I’d just received from Troy Hibbitts. He and his dad, Terry, had recently photographed an odd Spiketail (Zoraena sp.; formerly Cordulegaster) in East Texas—a female that didn’t seem to fit any known species from the area. The photos were intriguing. We all looked at each other and thought, why not? Since nothing was flying in the Valley, we decided to chase this mystery dragonfly instead.

Nearly 500 miles and more than eight hours of driving later, we rolled into East Texas. The next day, at Boykin Springs Recreation Area near Jasper, we met up with Martin Reid. Nick netted a male of the mystery dragonfly, and we collected a few more before the end of the season.

Sarracenia Spiketail hiding behind a pale pitcher plant (Sarracenia alata) at Boykin Springs Recreation Area (the type locality) (Angelina Co., TX), 7-April-2016, Photo by John C. Abbott.

Sarracenia Spiketail at Middle Branch Bog (Natchitoches Parish, LA), 18-March-2011, photo by John C. Abbott.

It was clear we had something new. Between field trips, I shuttled the Donnellys back to Austin and taught a class, but we weren’t done yet. The following week, Greg, Kendra Abbott, and I were headed to Big Bend for a Colima Warbler census—and decided to take the long way, a 600-mile detour through Jasper, to look for the spiketail again.

As it turned out, Troy and Terry weren’t the first to photograph this species. The year before, Rick Nirschl had captured it in Big Thicket National Preserve (OC#312438), and in early April 2010, Gary Spicer photographed one at Gus Engeling Wildlife Management Area (OC#318429). Both records had been uploaded to Odonata Central but were originally identified as Twin-spotted Spiketails (Zoraena maculata). It was a great reminder of how powerful community science can be—and how, just like in museum drawers, discoveries are waiting to be found in digital archives too.

The next year, we focused on finding more populations. All three initial sites—Boykin Springs, Gus Engeling Wildlife Management Area, and the Pitcher Plant Trail in Big Thicket—had one thing in common: the presence of pitcher plants (Sarracenia alata). That gave us a big clue. Joined by U.S. Forest Service wildlife biologist Steve Shively and his family, we formed a strong Spiketail search team.

Sarracenia Spiketail (Zoraena sarracenia) search team at Peason Ridge Wildlife Management Area (Natchitoches Parish, LA). From left to right: Terry Hibbitts, Marla Hibbitts, Troy Hibbitts, Steve Shively, Micah Shively, Seth Shively, Tanya Shively, Greg Lasley, Kendra Abbott, and John Abbott. 18 March 2011, photo by John C. Abbott.

Before long, we’d found the species in Louisiana too—most notably at Middle Branch Bog in Kisatchie National Forest, home to a stunning community of pitcher plants.

Pitcher plants in Sarracenia Spiketail habitat at Middle Branch Bog (Natchitoches Parish, LA), 28-Mar-2017, Photo by John C. Abbott

Later that year, Troy and I formally described the species (Abbott & Hibbitts, 2011) and named it Cordulegaster sarracenia—the Sarracenia Spiketail—in honor of the pitcher plants it is so often found with. It is most closely related to Say’s Spiketail (Zoraena sayi). Note that in 2025, Schneider et al. moved nearly all North American Cordulegaster species, including sarracenia, into the genus Zoraena.

The nymph lives in shallow, mucky rivulets within bogs. I’ve done quite a bit of rearing and plan to publish some of the life history details soon.

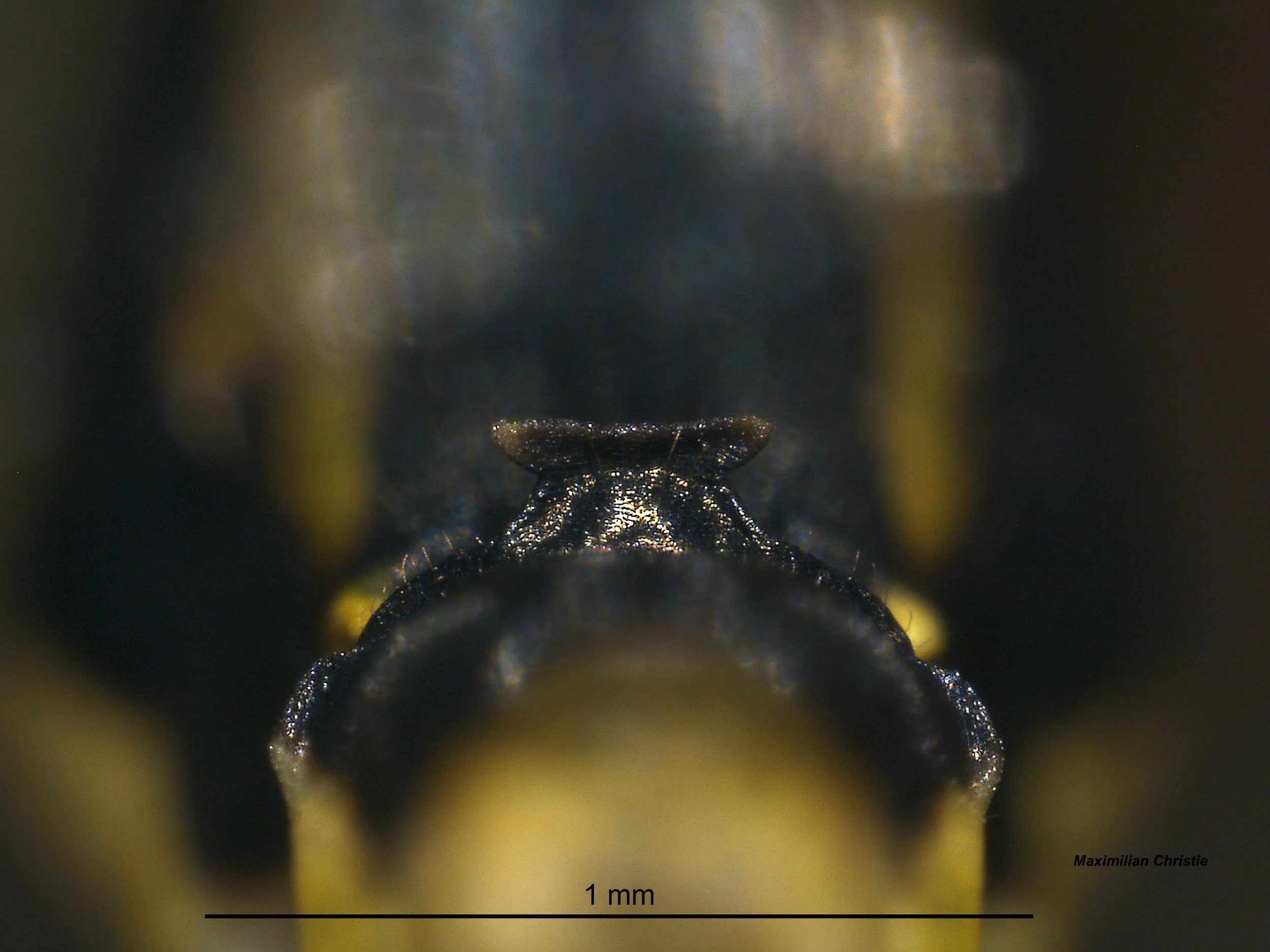

Sarracenia Spiketail (Zoraena sarracenia) nymph, 14-Apr-2017, Photo by John C. Abbott

Kendra Abbott and I have also studied the population genetics of the species and, unfortunately, found very little genetic diversity.

In 2016, the Southeastern DSA meeting was held in Alexandria, Louisiana, with the Sarracenia Spiketail as one of our main targets. It was a productive and fun meeting—participants were thrilled to see this rare dragonfly in person.

Sarracenia Spiketail (Zoraena sarracenia) female hovering while looking for an oviposition location (Middle Branch Bog), 5-April-2016. Photo by John C. Abbott.

Since then, new sites have been found in eastern Texas and western Louisiana (see current distribution here), but its range remains limited. Still, every record feels like a small victory for this remarkable species, born from a rainy detour and a spark of curiosity.

Our December blogger is John C. Abbott, Associate Professor, Chief Curator and Director of Museum of Research and Collections at The University of Alabama. John is the author of five books, including several specifically on Odonata, and the Princeton Field Guide to North American Insects. He is Managing Editor of the International Journal of Odonatology. Contact John at jabbott1@ua.edu.

References:

Abbott, J. C. and T. D. Hibbitts. 2011. Cordulegaster sarracenia, n. sp (Odonata: Cordulegastridae) from east Texas and western Louisiana, with a key to adult Cordulegastridae of the New World. Zootaxa(2899): 60-68.

Schneider, T., A. Vierstraete, O. E. Kosterin, D. Ikemeyer, F. S. Hu, R. Novelo-Gutierrez, T. Kompier, L. Everett, Jr., O. Muller and H. J. Dumont. 2024. Molecular Phylogeny of the Family Cordulegastridae (Odonata) Worldwide. Insects 15(8).https://doi.org/10.3390/insects15080622